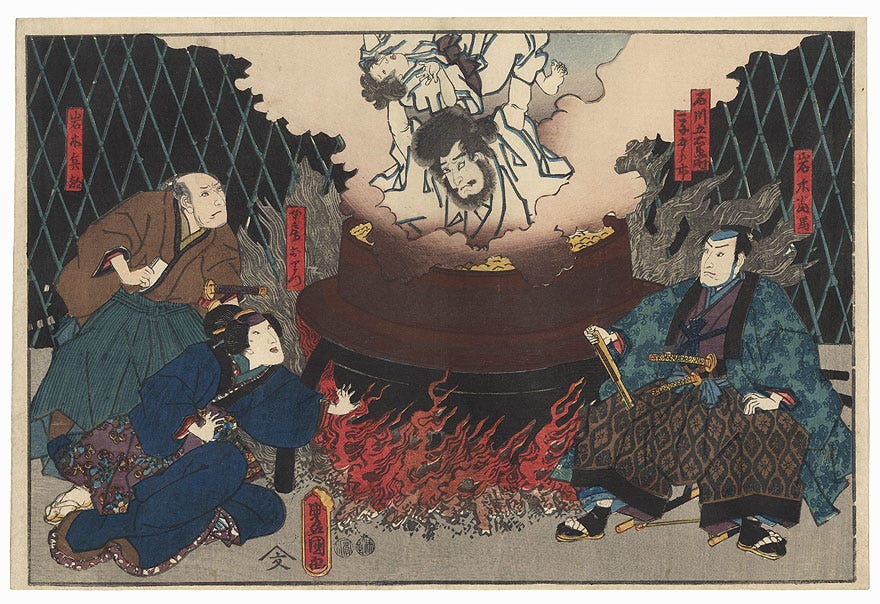

Ishikawa Goemon: Robin Hood Boiled Alive!

Goemon versus the famous torture technique

Ishikawa Goemon (石川 五右衛門) is often called the Robin Hood of Japan. That’d be accurate, if Robin Hood were a ninja, could fly, inspired James Bond villains, and gave his name to a deadly hot tub.

Most of what we know about Goemon’s life is passed down through folktales and kabuki plays, both of which are of course well known for their historical accuracy. We’re certain of quite a bit of nothing about Goemon’s life, so consider this article a kind of Choose Your Own Adventure, where every path ends in “Well, sort of, maybe, depending on whom you ask.”

Goemon was born around 1558 in Iga...or in Enshu. He was born a samurai...or a ninja...or neither. He studied ninjutsu (the art of dressing in black pajamas, throwing little stars, and being historically inaccurate) and seduced his master’s wife...or mistress...or maybe just stole his master’s special sword.

Anyway, look, Goemon had to go into hiding for REASONS, and became a bandit. But, like Robin Hood, he virtuously stole from the rich and gave to the poor! ....or he stole from anyone and threw valuables around when the authorities were getting too close, to create chaos and escape.

OK, but he definitely stole stuff.

And then he committed the second most significant crime of his life: he tried to kill Oda Nobunaga (織田 信長), one of the Three Great Unifiers of Japan. He hid in the ceiling above Nobunaga’s bed like the world’s least romantic mistletoe, and let poison drip down a thread, aiming for the sleeping Nobunaga’s mouth. Actually it’s pretty unlikely this happened, but Roald Dahl was inspired by the idea and used it in the screenplay for the Bond film You Only Live Twice, so this is the Goemon story every gaijin knows.

In contrast, the story every Japanese person knows about Goemon is that he was boiled alive.

This time, he had snuck into the bedroom of Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豊臣 秀吉), the second of the Three Great Unifiers. Goemon hated Hideyoshi because he held him responsible for his wife’s death...or his father’s death...or maybe he just disliked despots. Naturally, being a ninja-or-samurai-or-neither Goemon was going to kill Hideyoshi...or steal some valuable bauble to minorly inconvenience the fabulously rich lord. Unfortunately, in a very non-ninja-like way, Goemon knocked over a bell, or knocked over a boring, pedestrian, non-magical incense burner, or, in a much more ninja-like way, didn’t knock anything over but was exposed by a very interesting, unusual, magical incense burner which alerted all the guards.

In any case, Goemon was sentenced to death, together with his young son. He was invited to take a nice, warm bath in a big cauldron by the riverside and gradually the bath was made considerably less nice and considerably more warm.

Goemon held his son above the boiling liquid (water or oil—what, you’re surprised the stories can’t agree?). Your choice of ending at this point are non-happy or really non-happy: the executioners were impressed by Goemon’s bravery and took pity on the boy, saving him; or the executioners were unimpressed and simply watched until Goemon dunked the boy in the boiling liquid, ending his suffering as quickly as possible.

Goemon is supposed to have composed a death poem (辞世, jisei) before his execution, and it’s kind of awesome:

石川や 浜の真砂は 尽くるとも 世に盗人の 種は尽くまじ

Even if the sands on the shore of Ishikawa run out, the seeds of thieves will never run out.

In other words, “maybe you caught me, but there’ll always be thieves, suckas!” Goemon then dropped the brush like a mic, truly the O.G. of O.G.’s.

Strangely, Goemon never got around to trying to kill Tokugawa Ieyasu (德川 家康), the third unifier, but two out of three ain’t bad.

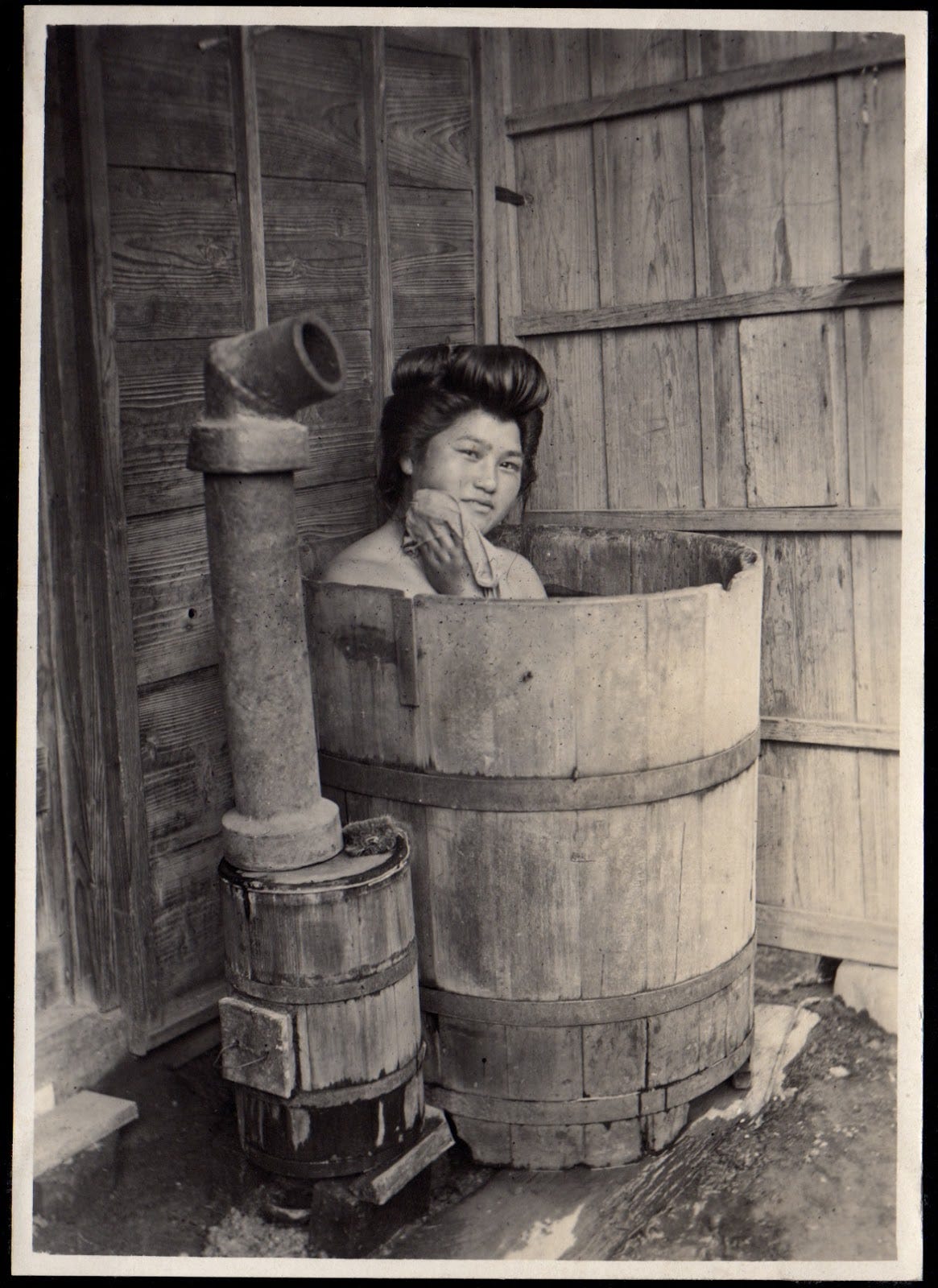

Today, Goemon survives in lots of manga and anime (master swordsman Goemon Ishikawa XIII in Lupin III), video games (がんばれゴエモン, Ganbare Goemon!), and novels and films (the Shinobi no Mono (忍びの者) series). Unlike Robin Hood, he is sometimes the hero and sometimes the villain. But his most important legacy is that round bathtubs heated from below are still called goemonburo (五右衛門風呂, “Goemon bath”).

References

Adams, Andrew. Ninja, the Invisible Assassins. Los Angeles, Ohara, 1970, pp. 37, 47, 160. https://archive.org/details/ninjainvisibleas00adam/

Clark, Scott. Japan, a View from the Bath. U of Hawaiʻi Press, 1994, pp. 46–47.

Joly, Henri L. Legend in Japanese Art. John Lane, 1908, pp. 101–102. https://archive.org/details/legendinjapanese00jolyuoft/page/101/mode/1up

Morse, Edward S. Japanese Homes and their Surroundings. Harper, 1889, p. 193.

Sasaguchi, Rei. “A rogue on high.” Japan Times. 2010-03-05. https://web.archive.org/web/20190107152502/https://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2010/03/05/stage/a-rogue-on-high/

Thornton, S. A. The Japanese Period Film: A Critical Analysis. McFarland, 2008, pp. 96–97.

Turnbull, Stephen. Warriors of Medieval Japan. Osprey, 2005, pp. 168 & 180.

The details about this guy's life, adventures, and morality are so varied and contradictory that it reminds me of someone else, but I can't quite think of who it is. Oh, Jesus, never mind.