Kai-ōi Game: When Fancy Ladies Played With Their Clams

Seafood is delicious, but don’t throw it away right after eating. The elites of Medieval Japan used the carcasses of sea creatures for a nefarious reason: playing a game.

Last time we saw how the courtly incense-awase turned into the simpler jishu-kō and Genji-kō. This time, let’s look at how shell-awase (a refresher on awase) devolved into kai-ōi (貝覆い, “shell covering”), using sets of hundreds of paired clam shells.

After forcibly evicting the clams from their homes (and relocating them to human stomachs), the homes were torn apart into halfshells. One halfshell was called the jigai (“base shell”), the other dashigai (“deal shell”).

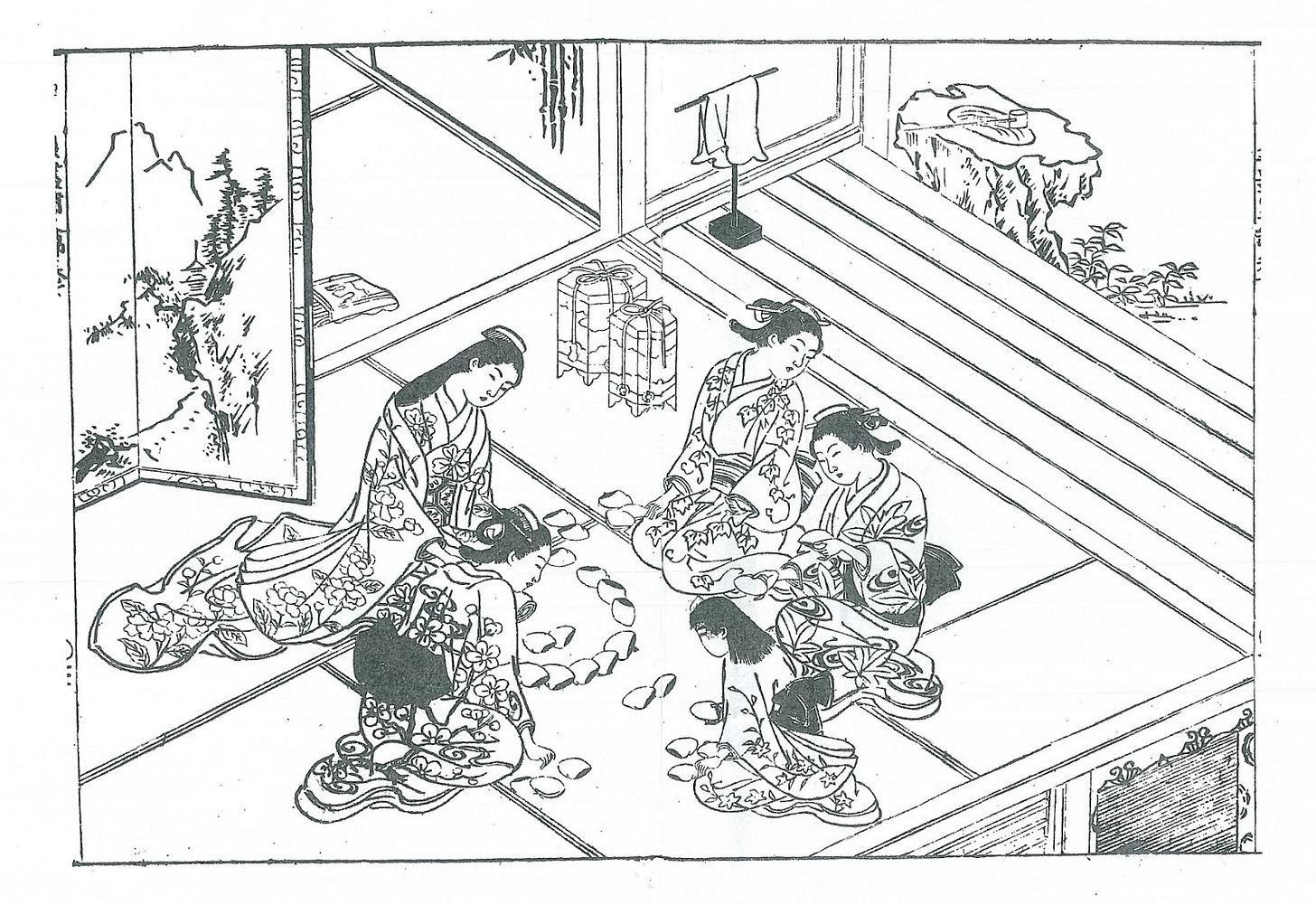

The jigai were placed in a large circle on the floor, with their boring grey-brownish outsides facing up. On each turn, a dashigai was dealt into the center of the circle. Players tried to visually find a matching jigai. The first player to find a match picked up the center dashigai and claimed it by placing it on top of the matching jigai (“covering” it). They then picked up both halves and probably confirmed the match by closing the two halves together. If they fit perfectly, the player claimed the pair and the next dashigai was dealt. Whoever had the most matches at the end won.

A kind of crustacean Concentration, or mollusk Memory...but without the memory aspect. The rules were simple, but matching hundreds of nearly-identical grey-ish shells was probably quite difficult.

By the late 1400s or early 1500s, the insides of the shells were decorated with brocade fabric or paint.

At first these decorations did not affect the game. Still, the shells were painted in pairs, with the matching halves having either the same or related scenes. It was more natural and less mind-numbing to start playing the game with the shells inside-up, matching the pretty paintings rather than the boring outsides.

Predictably, scenes from The Tale of Genji were common decorations. It’s as if no other popular franchise existed. George Lucas hasn’t milked Star Wars as hard as people were milking Genji.

Around the same time, someone got the bright idea to write tanka poems on the insides of the shells. Whether this happened before the fabric and paint idea or later is unclear. We have a reference from 1489 mentioning writing poems on shells, though. Tanka poems have two phrases: the first phrase would be written on one half shell, and the second on the other half. Matching these shells now meant flexing not just eyeball muscles, but also your literary muscles.

By the 1600s, really rich brides of the upper nobility had kai-ōi and jishu-kō sets in their dowries and the two games became associated with ideal femininity. Gradually, this custom spread to poorer and more productive levels of society. Edo-era books that described the behavior of a “proper” woman, like Illustrated Encyclopedia for Women (女用訓蒙圖彙) and Woman’s Treasury (女重宝記), included sections on both games.

Through the inclusion of Genji, tanka poetry, and the link to femininity, these two games gained back some of the cultural refinement that was lost when they replaced mono-awase.

Did you know that my Patreon has MORE articles and members-only videos (like the one about fart battles)? Check it out here!

Actually there is a modern version of this (tradition) called karuta. There will be 2 cards (these are made of paper) . One will have a phrase and the starting letter (hiragana or katakana) will be emphasized. Another will be a picture card that will have a relation to the phrase and also include the letter as well. All the cards are presented face up and people have to grab the pairs.

The following page links to one of the most valuable karuta cards ever made. A 1949 karuta card set that featured Babe Ruth (Ruth died in 1948 and was extremely popular in Japan

https://prestigecollectiblesauction.com/bids/bidplace?itemid=5677