One of Kabuki’s Most Famous Plays

Origin of "Shibaraku"

Shibaraku (暫, “Just a moment!”) is one of the best-known and most performed kabuki plays. If you’ve only ever seen one picture of a kabuki character, it’s probably the hero from Shibaraku.

The play an action comedy in the aragoto (荒事) or “rough style,” with lots of big fancy costumes and make-up, exaggerated movements and poses, and an over-the-top magical hero. Think Schwarzenegger movie, but with punny speeches instead of one-liners.

Like Hollywood’s action comedies, Shibaraku has a pretty simple plot: evil dude gives a speech about the bad things he’s about to do (a bad guy without a monologue is like a tanuki without its balls), is interrupted by a call of “just hold on a damn second!” (“Shibaraku!”) from off-stage, hero enters, hero delivers rousing speech, hero lops off a bunch of heads with a comically large sword (think Final Fantasy, the thing is taller than him!), hero exits, curtain.

It didn’t quite start that way, though.

The anecdote goes that in the late 1600s the famous actor Danjūrō I was performing in a play with his co-star and rival Heikurō I. Heikurō supposedly tried to steal the scene by not giving Danjurō his cue to enter. Danjūrō shouted “Shibaraku!” (“Just a moment!”) from off-stage, and strutted onto the stage like he paid the rent for the entire theater. The fans lost their minds and coin pouches, so Danjurō started doing it in other plays, too.

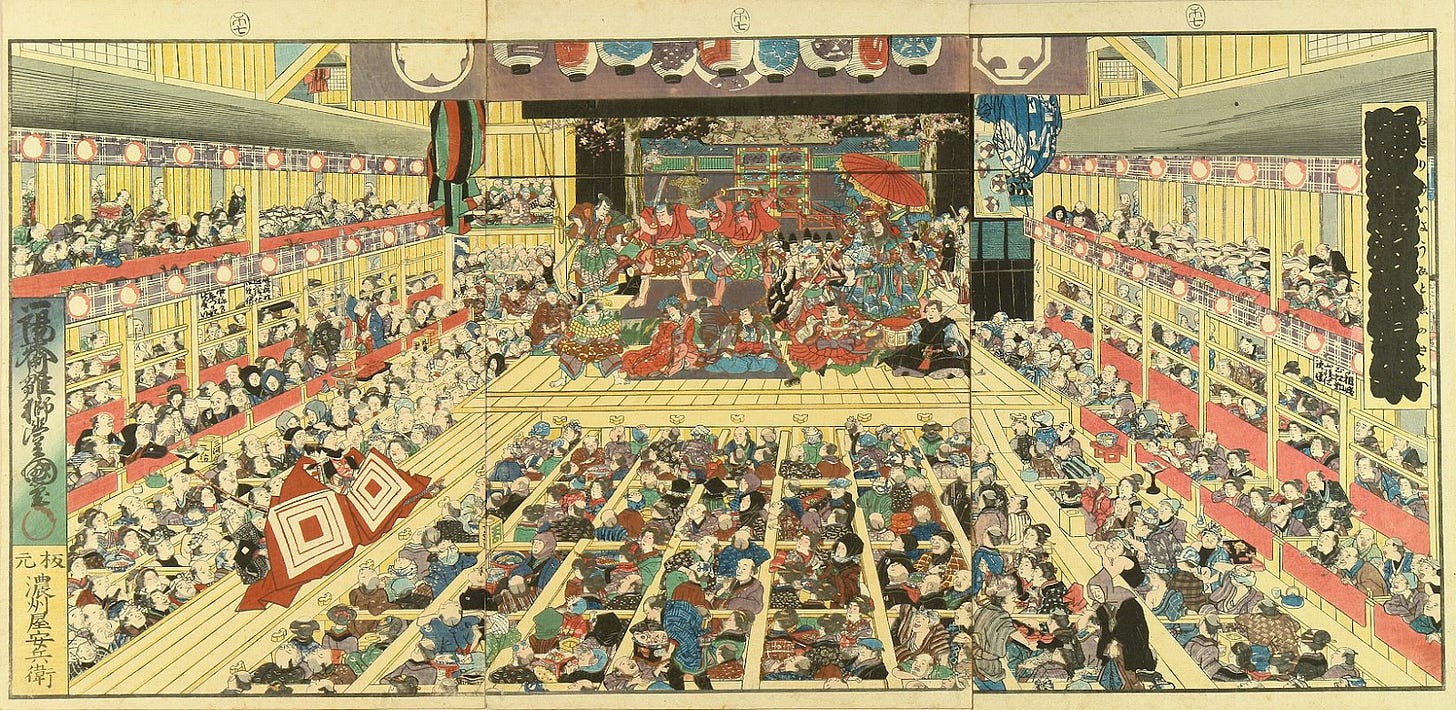

Danjūrō’s entrance was extra effective because he entered on the hanamichi (花道, “flower way”), a catwalk that extends from the main stage. Originally it was only a temporary plank used by actors to walk into the audience and receive flowers, but it quickly became a standard way for characters to enter and exit—and Shibaraku’s popularity is probably part of the reason.

The Shibaraku scene was used for the next few hundred years, in various plays. Kabuki plays were flexible, with no fixed canonical text. A popular scene like Shibaraku could be dropped in any play, like a Bollywood musical number.

Throughout the 1700s, all three of the big Edo kabuki theaters included the scene in their important kaomise programs. Kabuki contracts for actors and musicians lasted one year, starting in the 11th lunar month. Kaomise (顔見世, “face-showing) is the celebration of the start of a new theatrical year and the plays put on are used to show off the actors and musicians hired for that year.

Shibaraku is particularly good for kaomise, because it contains several roles of each type (heroes! villains! women!), and has a big crowd scene. It’s great for showing off a lot of talent at once.

Until 1840, Shibaraku was always part of a larger play, and the exact plot and names of the characters varied wildly year to year, but that year a standardized stand-alone version was immortalized in Danjūrō VII’s influential book of 18 great kabuki plays (歌舞伎十八番). In 1895, during the Meiji era, Danjūrō IX revised the play into the version that is performed to this day: it includes a stolen seal, a fake sword, a bumbling priest, lots of breaking of the fourth wall, and a fancy twelve-fold decapitation in one dramatic swoop.

One bit of freedom remains: the tsurane (連ね), the dramatic, pompous, and humorous monologue given by the hero as he enters on the hanamichi is different in every production. Riddled with puns and tongue twisters, it is meant to show off the actor’s skill. Good fun for the whole family, all because of one petty actor’s beef.

References

Ernst, Earle. The Kabuki Theatre. University of Hawai‘i Press, 1974 (first published Oxford UP, 1956).

Brandon, James R. Kabuki Plays on Stage: Volume 1, Brilliance and Bravado, 1697–1766. Edited by James R. Brandon and Samuel L. Leiter, U of Hawaiʻi Press, 2002, pp. 42–65.

Salz, Jonah (editor). A History of Japanese Theatre. Cambridge UP, 2016, pp. 117–118, 123, 420.

Matsunosuke, Nishiyama, and Gerald Groemer. Edo Culture: Daily Life and Diversions in Urban Japan, 1600–1868. U of Hawai’i Press, 1997.

Thornbury, Barbara E. Sukeroku’s Double Identity: The Dramatic Structure of Edo Kabuki, U of Michigan Press, 1982.

Kabuki can be surprisingly vulgar at times. Depending on the play, very earthy...