Poetry Etiquette (How to Survive the Heian Court)

Nowadays, poetry is a lost art only practiced by English majors and those who just upset their girlfriends really badly. But if you were a Japanese noble of the Heian period (794 - 1185), it was a weapon in a warzone called the imperial court. It determined whether you lived or died. Socially. Well, I guess indirectly poetry could determine whether you actually died, because it allowed you to make friends and allies, people you could count on to have a slightly lower chance of betraying you.

As a noble, you had to be armed with metaphors and similes, and, because the Heian dating scene was totally debaucherous, double entendres.

A proper gentleman or lady was expected to come up with poems on the spot, whether the person was bantering, flirting, or negotiating an alliance to backstab a brother.

“In spring, the plum blossoms bloom and fall.

Just like my brother, who never calls.”- Minamoto no Yoritomo probably, I wouldn’t put it past him

Courtship was done through poetry. Heian women could not show their faces in public to strangers, so a nobleman who was interested in a noble lady had little chance to talk to her. Instead, he had to send her a poem, wait for a response poem, then dissect the response like a student doing a literary analysis to figure out whether she was the woman of his dreams, or more likely, to see what he could write next to get under her sheets.

A woman receiving a poem was looking to see if her pursuer was intelligent, funny, and talented. A poem with overdone themes was seen as boring and was likely to be rejected.

Famous court lady and early blogger Sei Shōnagon had no mercy for bad poetry. She wrote that she lost respect for anyone who didn’t incorporate her references into his reply poem.

She also wrote:

It also dampens the spirit when you're leading a heady life in the swim of things and you receive some boring little old-fashioned poem that reeks of the longueurs of the writer…

Once you look up what “longueurs” means, you’ll see that, yeah, people were indeed judged harshly over their poetry.

Now if you're sitting there caressing your Creative Writing degree and thinking, I’m decent enough to survive in the Heian court, put down that Macbook Air for just a minute and step out of the time machine before you embarrass yourself.

You couldn’t just drop a poem you pre-wrote in the middle of a conversation. That would reek of trying too hard. There were rules. Simple rules, but important:

Poetry is a two-way street.

Prepared poems are different from live poems.

Live poems should be spontaneous.

Poetry goes both ways

The first rule, the foundation for most Heian poetry, the rule that would get you the dreaded awkward stare if you broke it, was reciprocity.

If you were talking to a friend and he breaks into a heartfelt poem about his love for his cat, how would you respond? After pushing away the intrusive thought that you have pretty weird friends, you would probably call his poem beautiful or ask him how long it took for him to come up with something this amazingly corny, depending on your friendship. Both of these would have been the wrong reaction.

Heian poems were not just meant to be enjoyed, they demanded a reply poem to complete the thought, answer a question, or take the topic to new heights.

Often, an opening poem was short and incomplete. It’d be like if someone says, “Roses are red, violets are blue” and then just stops. You can tell immediately the poem is dangling, and needs a few good lines to catch it: “I feel awkward, what about you?”

Here’s an exchange from The Gossamer Years (Kagerō Nikki) where the author, Michitsuna no Haha, writes her husband, Fujiwara no Kaneie, a poem:

Because the wild waves

have rolled in to ravage

the beach it once trod,

no longer does the plover

leave its tracks in the sand.

The plover here is her husband Kaneie. He had left a book at her place and sent a person to pick it up. She was unhappy that Kaneie rarely visited, and wrote the letter to say, basically, “Why don’t you come more often, you big meanie?”

He responds with,

You may return the book,

thinking my affections have strayed,

but the beach plover

wishes to leave its tracks

on no other shore than yours.

“Baby, you’re the only one for me.”

She hits him with a snarky reply:

Were I to seek

the place where the beach plover

leaves its tracks these days,

I would doubtless see many shores

as I sought to find the way.

Why? Because Kaneie was a big ol’ shore hopper, visiting different shores as often as I visit boba tea shops.

Poems invited conversation. You had to incorporate the imagery and themes of the initial poem in your reply. Going back and forth using metaphors and wordplay made things fun. Probably why it was perfect for flirting.

Not responding to a poem would be like if someone offered you a fist for a fist bump and you just left him hanging. Not responding to a potential lover’s poem meant a rejection.

Prepared vs live poems

Expectations were different depending on whether you prepared a poem in the comfort of your own home and then sent it out, or you came up with the poem on the spot.

A live poem didn’t have to be one recited verbally, it could be written. Say, you’re at a party and you see a cute guy with nice makeup and even nicer career. You may decide to jot down a poem on a piece of paper and tell a maid to hand it to him.

Now you might expect writing a prepared poem to have been much less stressful—no rush and plenty of time to consult the thesaurus. However, everyone knew this and so had much higher standards for prepared poems than live ones.

Speaking a poem aloud might have been a better idea than writing one. In a dating scene where people mostly communicated by letter, where you didn’t have the benefit of seeing facial expressions and body language, you best believe people turned into L from Death Note reading into every brushstroke and crease for any morsel of information about the author they could find, real or imagined.

Was his calligraphy imperfect? His intelligence must be imperfect. Is there a smudge at the corner? Incompetent. Did he fold the letter one degree off a straight line? He’s a serial killer.

Don’t think too hard

So what about live poetry? You might have the impression that Japanese nobles walked around court like light-skinned Tupacs with PhDs spitting profound and colorful bars, but that actually did not happen.

Most poems created on the spot were just “meh.” People usually treated it like how we would treat tossing out a joke, not like they were performing for a competition. No one expected a lyrical masterpiece. The standards were much lower than written poems. Of course, we’re talking about Heian standards here. Their idea of low standards was closer to your Asian classmate’s idea of low test scores.

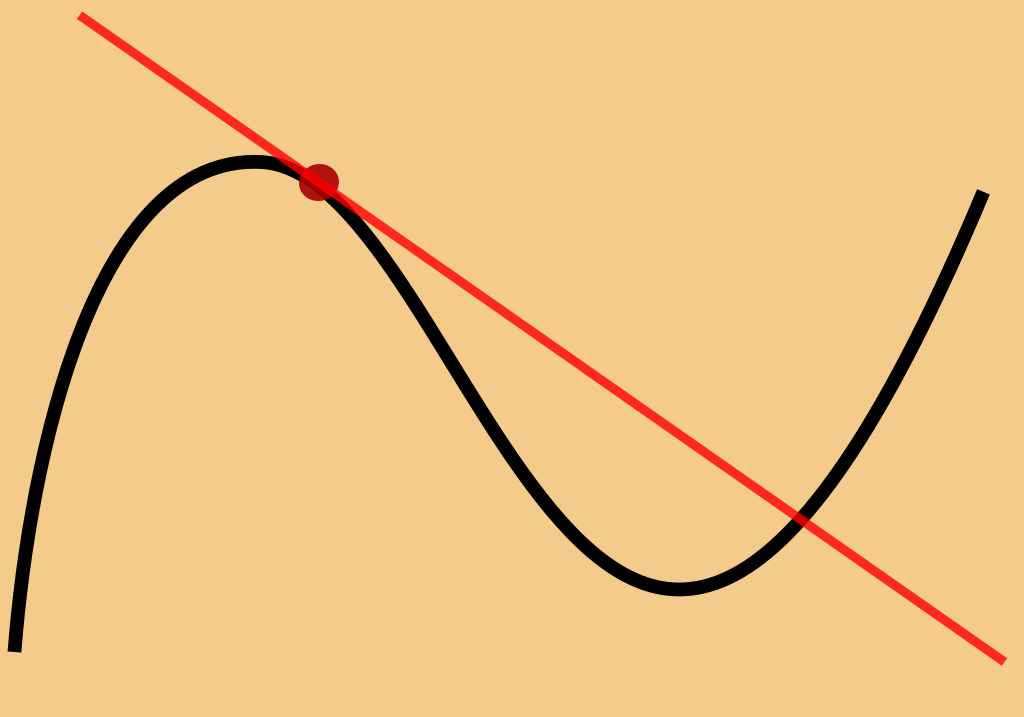

The lower standards were okay because of the third rule on our list: spontaneity. You had to treat a live poem like a derivative. Yes, the calculus kind.

A derivative (the red line).

A derivative is the rate of change of a function at one instant in time. To find it, you must look at a single point in time, not one millisecond before or after. A poem must feel like it was born that very moment.

A lady receives a flirt

This scene of a noble attempting to flirt, from The Pillow Book (Makura no Sōshi), demonstrates this idea (and other poetical dynamics).

During a festival, the ladies dress in indigo robes and sit behind their blinds, as usual, enjoying the performances. Lady Kohyōe’s cord comes loose and she asks for help, expecting a friend or a maid to fix it, but a Captain Sanekata walks up to her and boldly ties her cord. A solid first move, Captain.

Then this man who likely remembers people’s birthdays tells her a poem:

A wintry indifference

freezes the mountain well's blue waters

to a knot of ice.

How might I melt that cord

and loosen its icy knot?

Can you guess what that means? If not, fear not, daddy’s here’s to help.

I don’t know what he did before, but Captain Sanekata’s current job is clearly being captain of wordplay. The poem uses the term 山井 (“mountain well,” pronounced yamai). Yamai is also the pronunciation of “mountain indigo,” a plant used to make indigo dye. And what is Lady Kohyōe wearing? Yep, indigo.

The frozen well water in the poem refers to her cold demeanor. “You’re so cold to me,” Sanetaka is saying in the first half of the poem.

Sanekata also uses the character 紐 (“cord,” pronounced himo). It also happens to be the pronunciation of “ice surface.” Saying he wants to melt that cord means he wants to melt her icy surface. There’s also an additional scandalous meaning of wanting to remove the cords holding her clothes together.

So to these clever verses, what does Kohyōe say in response? Nothing. Not a word. Maybe she’s young and unused to being hit on so publicly, or maybe her tongue has strayed into the path of a sudden wave of embarrassment, but she says nothing back.

Now if a person had trouble coming up with a response, it was polite for someone else to compose a poem on the dummy’s behalf. And that does not happen here. Sanekata goes back to his seat.

The minutes slip by, sneaking expectant glances at Kohyōe as they pass before tiptoeing on. Awkwardness hangs about the room. A messenger even skulks over to ask one of the ladies (not Kohyōe, of course) when the reply poem might be ready. He walks around all stressed out like a husband in the hospital waiting room unsure whether his wife is going to give birth safely or she doesn’t exist.

Luckily, our girl Sei Shōnagon is sitting nearby. She wants to respond for the poor girl, but does not know if she can match the poetic firepower of Sanekata. However, she reminds herself of an important truth: it is better to think of a poem in the moment than to create the perfect one. One should not take too long. A good poem comes spontaneously.

She writes one and has another lady deliver it verbally:

The cord's knot is loose

as ice on the water's surface.

It finds itself undone

by the warm sunlight of a garland

of festive fern leaves in the hair.

Shōnagon plays with the ice theme. The cord’s knot is loosening, and so is the ice. The term for “sunlight” is pronounced hikage, but it also means a type of fern. Sanekata and the other men in the ceremony wear garlands with this fern design. Wonderfully improper.

Sadly, it was all for naught because the anxious lady she sends to recite the poem gets so nervous that her words come out like the stapler guy from Office Space. Sanekata keeps asking, “Huh? What? What’d she say?” Fortunately, the woman compensates by reciting it more impressively, which successfully makes her stutter something fierce.

Witnessing this sorry sight, Shōnagon is actually relieved he didn’t hear her poem because she thinks it’s pretty bad. Ma’am, if that’s bad writing, may my YouTube video scripts be as badly written.

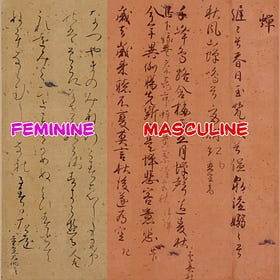

You may think the rules of poetry were harsh, but even more strict was the language you had to write in. Click here to see the difference between masculine and feminine writing.

Feminine vs Masculine Japanese Writing

The image shows men’s handwriting on the right, and on the left is my doctor’s handwriting.

Did you know I have a Patreon? You can find more articles like this, and exclusive videos like this new one debunking a persistent myth about Japan.

References

Bowring, Richard (1996). The Diary of Lady Murasaki.

McKinney, Meredith (2006). The Pillow Book.

McCullough, Helen Craig (1991). Classical Japanese Prose: An Anthology.