The Surprising History of Rock-Paper-Scissors

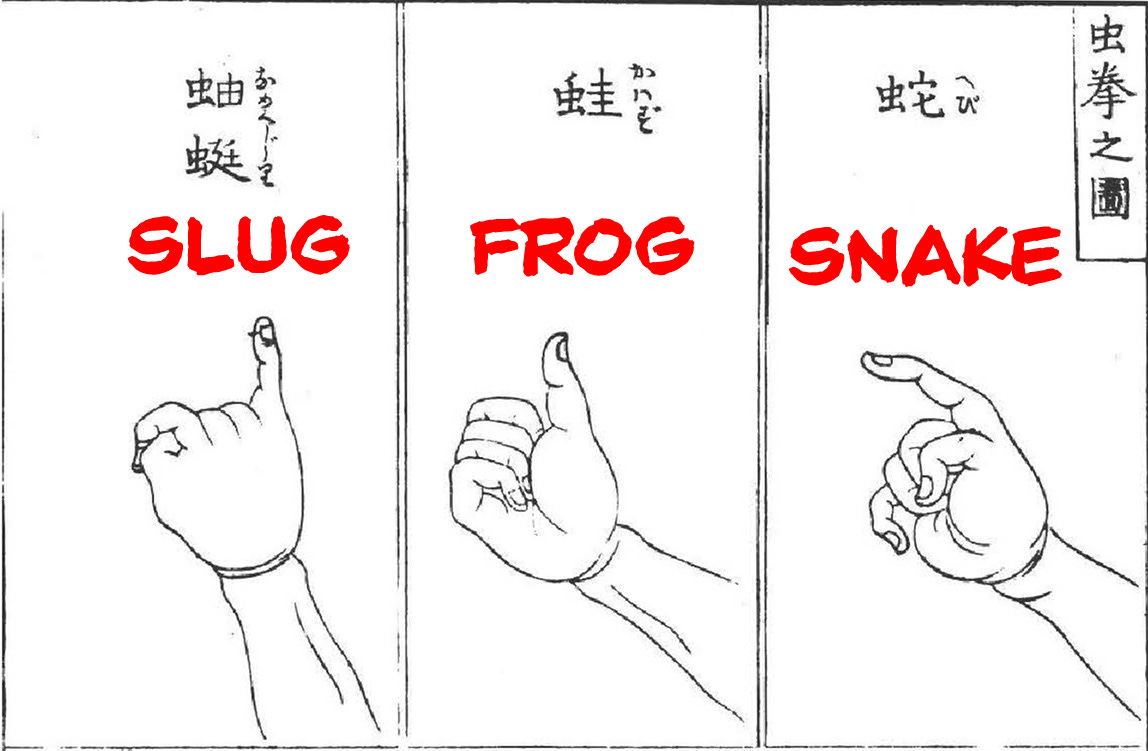

Slug-Frog-Snake!

Did you know rock-paper-scissors came from Japan?

A game called mushi-ken (虫拳, “bug fist” or “small animal fist”) appeared in Japan in the 1300s or earlier, and like all good things (kanji, ramen, TikTok) came from China. It’s a gruesome spectacle: a violent battle to the finish between snakes, frogs, and slugs! Snakes eating frogs! Frogs devouring slugs! Slugs...uh...slowly...oozing on snakes. OK, it’s just rock-paper-scissors with different gestures (index, thumb, pinkie), but admit it, it got you excited.

So why does pinkie (slug) beat index (snake)...? The main theory is that somebody done goofed hard. The Chinese characters for “extremely deadly and terrifying centipede you don’t want to see crawling on your futon” (蜈蜙 or 蚰蜒—it’s so terrifying it has multiple names) were mistaken for those of “harmless but quite disgusting oozy slug you also don’t want to see crawling on your futon” (蛞蝓).

In Chinese tradition, centipedes are believed to eat snakes’ brains. (That this isn’t entirely insane can be seen in this disturbing YouTube video that I encourage you to not click.)

Over the centuries, mushi-ken evolved into a family of games called sansukumi-ken (三すくみ拳, “three afraid of one another”). The most popular were kitsune-ken, tora-ken, and jan-ken.

In kitsune-ken (狐拳, “fox-fist,” also called tōhachi-ken, 東八拳) the fox beats the village head who beats the hunter.

In kitsune-ken you use both hands, like miming two adorable little fox paws for the fox, or aiming an adorable gun for the hunter.

If you’re in Asakusa during a festival you may stumble upon a mini sumo ring where ranked members of the Tōhachi-ken Association of Japan do furious battle.

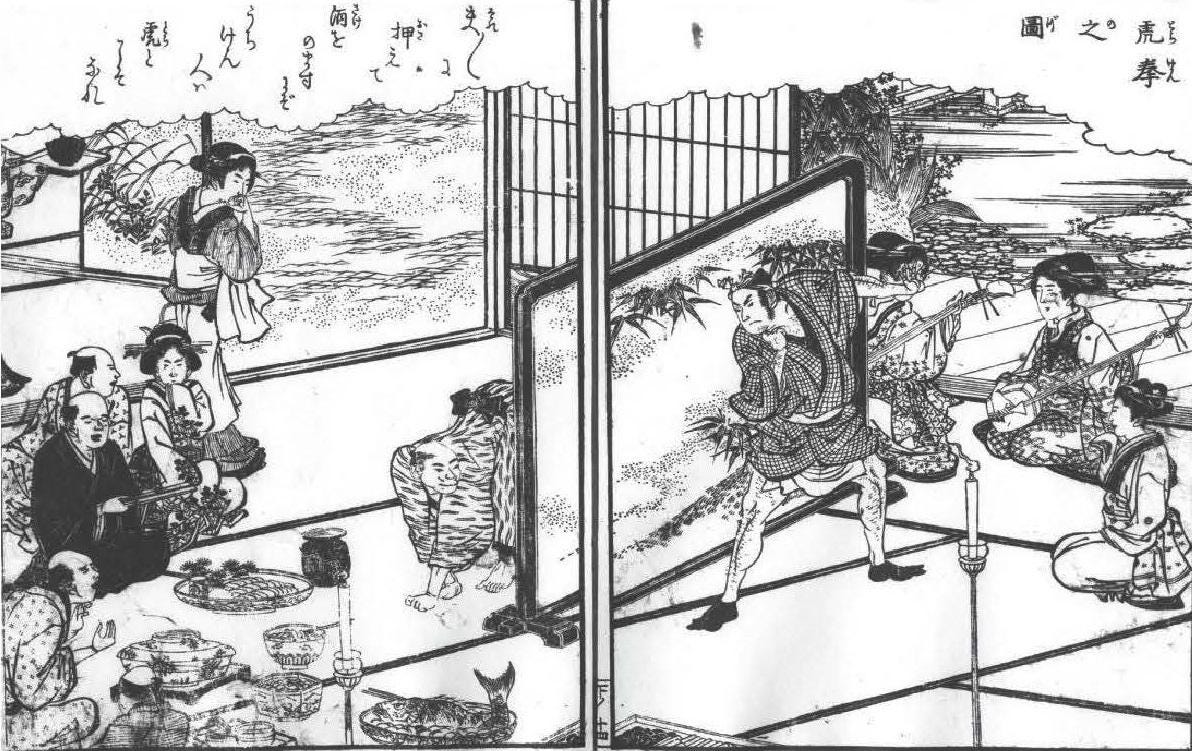

Tora-ken (虎拳, “tiger fist”) is not satisfied with mere hand gestures. It uses the entire body: Watōnai the pirate-warrior (loosely based on the historical figure Koxinga) walks upright and stabs with a spear, the tiger crawls on all fours, and Watōnai’s mother leans on a walking stick.

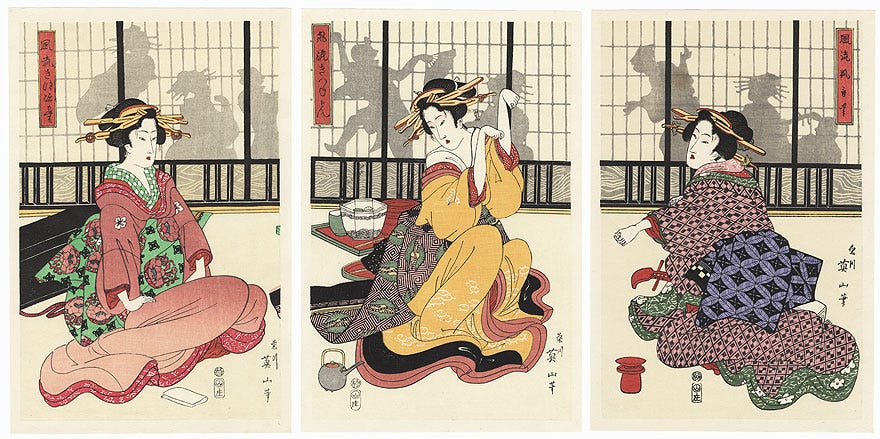

Naturally the warrior beats the tiger but is chastised severely by his mother for disappointing the family, choosing to become a pirate-warrior rather than a doctor-lawyer like his cousin. Since the whole body is used, players enter the room from three doors at once or hide behind screens until the showdown, usually at the end of a cheerful shamisen tune. You can still play tora-ken with geisha today.

Jan-ken (じゃんけん) is the one and only rock-paper-scissors: it slowly immigrated its way into the US in the early twentieth century, but it was not commonly played until the 1940s or 1950s. The New York Times still felt they had to explain the rules of rock-paper-scissors when the game was mentioned in a 1932 article about Tokyo.

During their heyday, ken games thrived in pleasure quarters like Yoshiwara in Edo and Maruyama in Nagasaki. They were played at drinking parties, and drinking a cup of sake was the standard penalty for losing a round.

In the 19th century there was a sansukumi-ken craze. After an 1847 kabuki play featured a sansukumi-ken song and dance, everybody went ken-mad. The whole country forgot about Genji for a while and instead concentrated on inventing new sansumi-ken games, making woodblock prints and composing songs about ken games.

These songs and prints often referenced current events or popular culture, but the games were always the same: they were almost all variants of jan-ken or kitsune-ken. Kind of like those novelty Monopoly sets with The Simpsons or Star Wars. One of the last was during WWII: a variant of jan-ken with warship, bomber, and bomb did the rounds.

After the war, jan-ken remained popular among children and as a quick way to settle a decision among adults. Nothing says “adult” like playing rock-paper-scissors to resolve conflict. Kitsune-ken and tora-ken were kept alive by only a few traditionalists.

Versions of jan-ken exist that can be played with the legs, or the tongue, or the bootie. This last one was developed for a Japanese TV show in 1992. What three gestures your bottom is capable of making remains a mystery, as no video of butt-janken appears to survive online: a tremendous cultural loss.

References

Brownell, Clarence Ludlow. The Heart of Japan: Glimpses of Life and Nature Far from the Travellers’ Track in the Land of the Rising Sun. McClure Phillips, New York, 1903, pp. 98–99. https://archive.org/details/heartofjapan00brow/page/98/mode/2up

Dilts, Marion May. “Commuting with Tokyo's suburbanites,” The New York Times Magazine, 1932-05-22, pp. 6 & 16. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1932/05/22/100744990.html?pageNumber=131

Linhart, Sepp. “Some thoughts on the ken game in Japan: From the viewpoint of comparative civilization studies.” Senri Ethnological Studies, Vol. 40, 1995, pp. 101–124. https://doi.org/10.15021/00003009

Linhart, Sepp. “Rituality in the ken game” in Ceremony and Ritual in Japan: Religious Practices in an Industrialized Society. Edited by Jan van Bremen and D.P. Martinez, Routledge, 1995, pp. 38–66.

Linhart, Sepp. “From kendo to jan-ken: The deterioration of a game from exoticism into ordinariness” in The Culture of Japan as Seen through Its Leisure. SUNY Press, 1998, pp. 319–344.

Linhart, Sepp. “Interpreting the world as a ken game” in Japan at Play: The ludic and the logic of power. Edited by Joy Hendry and Massimo Raveri, Routledge, 2002, pp. 35–56.

I deeply regret watching the YouTube video you said to absolutely not watch